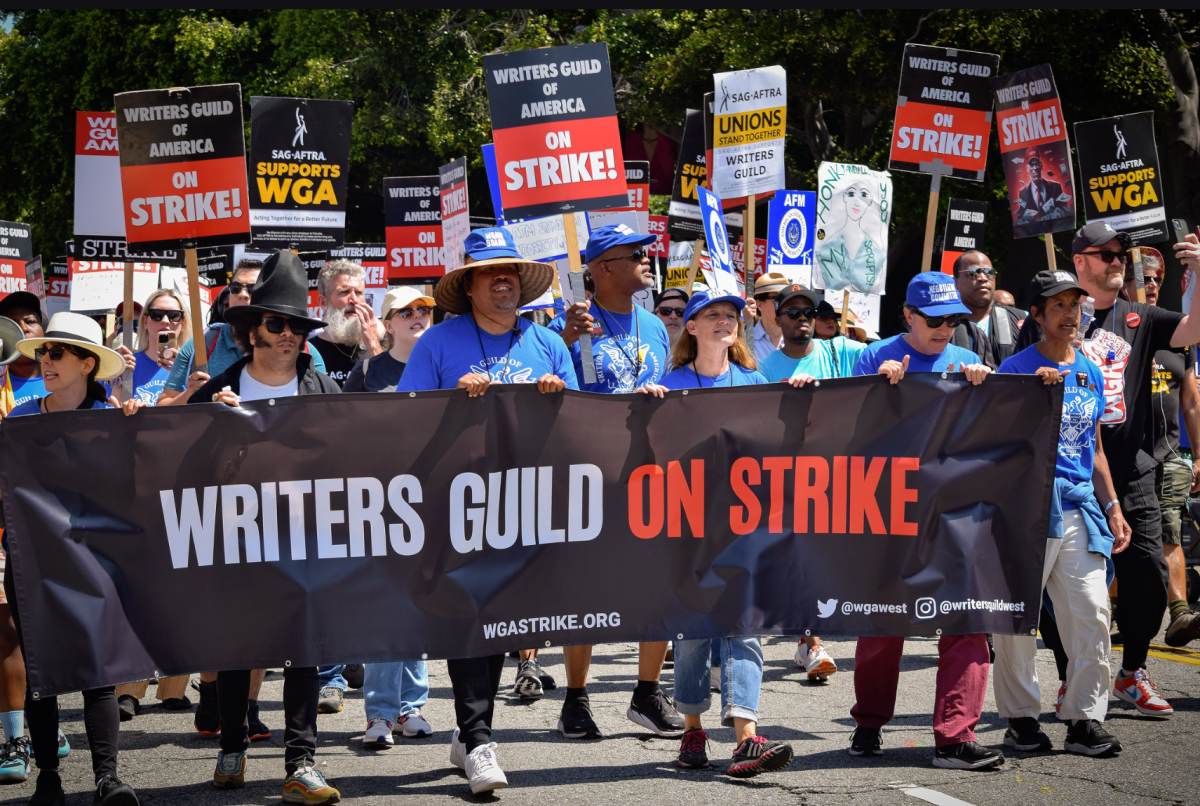

The WGA (Writers Guild of America) is a labor union formed in 1954 meant to protect the rights of writers. For 148 days, the WGA has been on strike, due to the overworked and underpaid treatment of these workers. The way these writers have been being treated affects every piece of modern day media, showing the dissent of Television and Film projects. Any and all productions in development have been postponed or canceled, but they have finally come to an agreement.

In current-day television, most series have shifted from 22 episodes per season to 8. While this may seem like a good thing for the writers, production companies have just doubled or even tripled the length of the project and the amount of work that has to be done. When negotiating with studios, the WGA proposed that they should have a 10-week minimum on any and all series with six writers in the room and argued that they should be allowed 3 weeks per episode. This proposal was declined with no counteroffers.

In the past, show runners and writers have come out with statements claiming that they and a few others were asked to write four episodes in the span of three weeks. When telling their story, a certain writer said, “In summer 2020, I worked a three-week mini-room for Apple TV. The showrunner, three other writers, and I were tasked with breaking an eight-episode season and writing four episodes. In three weeks.” Apple TV, which has an average budget of $3.1 million per episode decided to task only four people to do this job instead of hiring more writers and giving them a bit more time. The WGA was only requesting that writers get enough time to develop plots and allow shows to progress naturally, rather than rushing them and making them feel incomplete.

Then there is the issue of pay. Quite often, the studio decides on a budget for writers and has to fit however many writers into this budget. This would be a normal and understandable situation had the studios not decided to only pay writers about 2–3 percent of millions of dollars. A screenwriter wishing to remain anonymous made it clear that it was not enough. “So all told, that was 11 months, seven drafts, and 75K divided between me and my writing partner. We took out commissions, and we got 28K a piece. Before taxes. There is no such thing as a one-step deal.”

Streaming only makes this even worse. Residuals are paychecks sent to the creators of a project over time. They are meant to support and provide a somewhat consistent income to the people behind the success. When a show created by a streaming platform does great, the writers do get a small increase in residuals, but not enough. Now the problem arises when the show catches the attention of lots of people and brings more customers to purchase the service and bring in more money. No one but the production company is credited with this. Due to this observation, the WGA proposed that writers should receive a residual increase along with a fixed pay when their project is gaining more viewership, or when it’s the sole reason the platform is gaining more consumers.

Now we have come to our final issue, AI. With the development of technology, AI has become more popular. It has only ever been theoretical until these past few years, when we have seen it advance and become more commonly used in everyday life. It could vary from people getting ideas that AI comes up with to students writing their entire final essays with AI. There are not many things that can threaten the job of a writer; it’s a very complex role where you have to build entire worlds and develop characters in your head. But with the strike progressing and gaining more support, studios seriously began to threaten the idea of using AI instead of hiring writers. This would end the careers of any writers who do not want to become authors but want to work in the media and produce works of art that can be seen by the world. The WGA argued that AI should not be allowed to have a part in the works of film and television in any shape or form. Studios only countered with having annual meetings to discuss the advancements in technology. This would have given no guarantee that writers could keep their jobs and would still allow AI to become more developed.

After their initial meeting, the WGA finally went on strike, and a little over a month later, SAG-AFTRA (Screen Actors Guild—American Federation of Television and Radio Artists) joined them. Even though the writers were continuously threatened with the idea of studios shifting to strictly working with AI, the WGA held strong and kept their goal in mind. After lots of back-and-forth and constant discouragement until September 22nd, The WGA and AMPTP (Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers) entered a three-day meeting where they were to discuss all demands and attempt to put the strike to an end. At the end of this meeting, both groups were able to come to a tentative agreement. The picket line was suspended, and writers were not allowed to return to work. Until a few days later, when it was announced that the WGA and AMPTP had to come to a final agreement and the WGA had won.

In the end, the studios gave in and agreed to almost all demands made by the writers, securing their position in Hollywood and the media for years to come.